The Mickey Mouse Economics Of The Federal Reserve, Part 2

As we demonstrated in Part 1, the Fed’s financial statements are purely a case of Micky Mouse economics. After all, the laws of the free market militate mightily against the possibility of earning 1.40% on assets and paying only 0.07% on liabilities, as did the Fed in 2021. A 20X yield spread simply doesn’t exist in economic nature.

That year’s resulting $109 billion of phony Fed “profit”, therefore, needs be viewed as the smoking gun. That is, if the Fed’s financial statements are this preposterous why would we believe that its modern day macroeconomic management mission is any more legitimate?

In fact, when it comes to the Fed’s current “mission” we have another whole layer of hoodoo to unpeel.

The 12 reserve banks created by Congress in 1913 were called the “Federal Reserve System” for an obvious reason: Namely, that their essential purpose was to provide cash “reserves” to member commercial banks. In turn, by provisioning the commercial banking system with adequate reserves, the Fed would facilitate the process of credit creation by keeping the fractional reserve banking system of the day liquid and safe from credit-contracting panics and depositor “runs”.

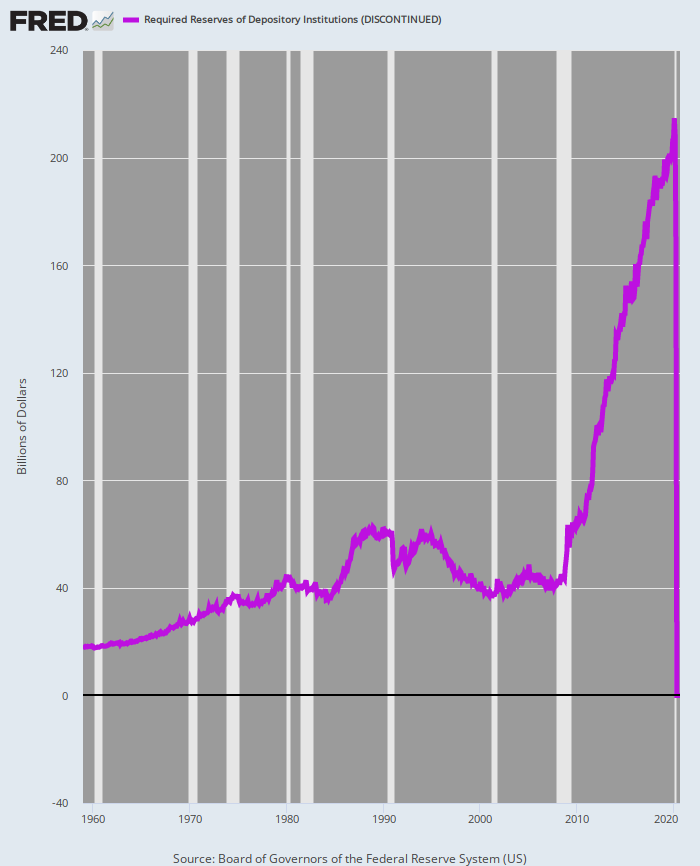

Alas, in March 2020 the Fed abolished the last remnant of “required” bank reserves on demand or transactions accounts. The new requirement of “zero” reserves replaced the previous arrangement in which reserve balances of 0%, 3% and 10% were required on ascending tiers of deposits based upon bank size.

In one fell swoop, therefore, upwards of $225 billion of traditionally “required” reserves were eliminated by a stroke of the Fed’s regulatory pen. Also, in one fell swoop the original mission of the Fed was eliminated, as well!

Required Bank Reserves, 1959 to 2020

That’s right. Save for the squalid fruits of mission creep described below, the Fed effectively put itself out of business when it cancelled “required” reserves.

So the history bears repeating. The original central bank created by Congressman Carter Glass and his colleagues was aptly termed a “bankers’ bank”. Its sole mission was to discount solid commercial loans originated by member banks so that the latter could readily access the cash needed to meet reserve requirements against their demand and savings deposits, which grew as their loan books expanded.

This is made abundantly clear in section 13 of the 1913 Act, which enumerates the “Powers Of Federal Reserve Banks”. Front and center was a focus on discounting commercial paper backed by goods in production or already shipped (i.e. receivables); and which paper also met such stringent standards for credit quality as the Fed might require.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to David Stockmans Contra Corner to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.