As we explained in Part 1, the Fed set itself up for what now amounts to $1 trillion of portfolio losses because it was unable to resist the pressure from Wall Street to print more and more cheap debt. Even when you set aside the so-called Great Recession period and the excuses for reckless monetary expansion conjured up by Ben Bernanke & Co., it is damn evident that the FOMC knew it was printing its way into catastrophic losses.

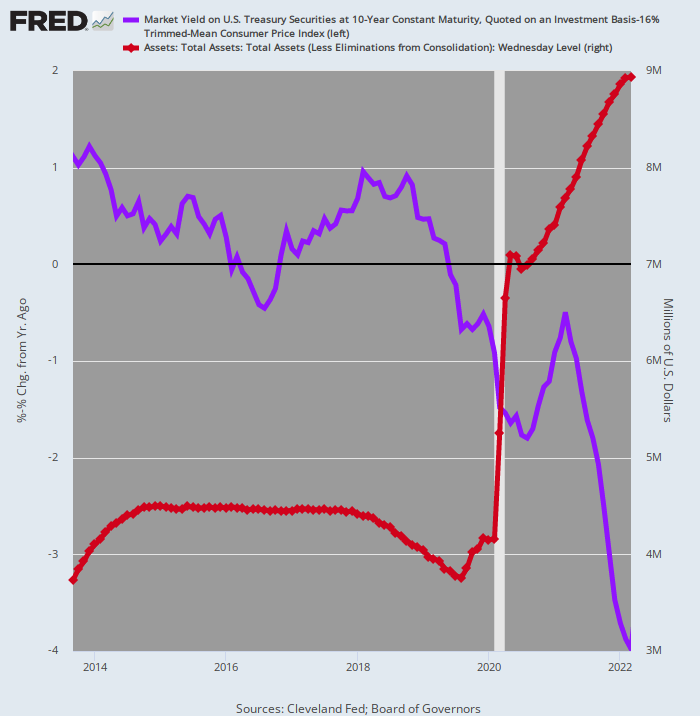

That’s because during the nine years between September 2013 (when the Great Recession “emergency” had long passed) and March 2022, when it finally pivoted to inflation-fighting, the Fed expanded its balance sheet (red line) by a staggering $5 trillion. That amounted to a growth rate of nearly 11% per annum, yet it occurred when the inflation-adjusted or real rate on the benchmark 10-year UST (blue line) was barely positive, and actually negative a good part of the time.

Supposedly, the 12-members of the FOMC were financially literate, and thereby understood that they were buying long term government and GSE debt securities which were way, way over-valued. And they also surely understood that these portfolio holdings would inevitably plunge to deeply discounted market values when interest rates were ultimately permitted to normalize.

So today’s $1 trillion of unrealized losses were not an unexpected accident; these losses were actually embedded in a deliberate policy design.

Fed Balance Sheet Versus Inflation-Adjusted 10-Year UST Yield, September 2013 to March 2022

Likewise, the claim that the Fed unavoidably lost control of its balance sheet during the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) and afterwards because its central banking duties required it to buy guaranteed loss-making public debt by the trillions is self-evidently malarky.

The fact is, during the 15-year period after 2007 its member banks had been drowning in deposits and excess reserves. They actually didn’t need a dime of new credit from the Fed in order to support their loan-making activity–-to say nothing of the $8 trillion of new credit actually printed by the FOMC between November 2007 and March 2022.

As shown in the chart below, total commercial bank deposits (red area) during this period nearly tripled, rising from $6.6 trillion to $18.1 trillion. By contrast, loans and leases (green area) outstanding only rose by 71%, meaning that the historical loan-to-deposit ratio of 97%, which prevailed at the beginning of the period, had sunk to just 61% by March 2022.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to David Stockmans Contra Corner to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.